“Oh moon in the deep sky,

your light sees far,

you roam over the wide world,

and peer into human dwellings.”

(Rusalka – Song to the Moon)

In the summer, shortly after I had returned from seeing Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte in Bonn, I asked my son if there was any opera that he wished to see. One of the two works he mentioned was Antonín Dvořák’s Rusalka, so I set about finding out where it was due to be performed. I discovered that the opera house in Ostrava was having a short revival of their production staging a small number of performances in November and December, so we started to plan how to take a brief trip to see one of them. Tickets for Rusalka went on sale in September, while I was away on my trip with my wife to the Baltic States – so to ensure that I secured the best seats, I bought them the moment that they went on sale while I was on an Estonian train travelling between Turku and Tallinn.

As Ostrava is served by only two flights a week from London, we decided to go via Katowice in Poland which has a much more frequent service.

Day 1 – Friday 28th November 2025 – London to Katowice

Our flight to Katowice was at 09:35. Unfortunately, the incoming plane landed about 20 minutes late, but not long after the last of the arriving passengers had left the aircraft we were ushered down the steps to make the short walk to board the plane. However, there was an unexplained delay before we were allowed on. Fortunately, because we were among the last to join the queue for boarding, our wait was under cover, unlike most of the other passengers who had to wait outside on the tarmac. We eventually departed at 10:25, 50 minutes late.

Initially the views from the plane were obscured by cloud, but at the German/Polish border the clouds cleared to reveal a very snowy landscape. From my side of the plane I had a good view of Wrocław, where I had been in 2022. The plane must have had a favourable tail wind, as it landed in Katowice at 13:05, just 10 minutes late. There was a lot of snow on the ground at Katowice airport and the temperature was still below freezing in the middle of the day. Although the plane pulled up next to the terminal building, we still had to be bussed to the entry point for non-Schengen arrivals, so that we could go through passport control.

We got through passport control quickly, in time to catch the 13:44 bus to the centre of Katowice, some 45 minutes away. It was noticeably colder than it had been when we left the UK. Buses run half-hourly and ours was crowded. I managed to get the last remaining seat, but my son had to stand. We got off at the first stop for Katowice’s cultural quarter.

To maximise our time we went straight to the Museum of Silesia. The museum occupies the site of a former coal mine, with the pit winding tower dominating the landscape. The main exhibition space of the Museum of Silesia is located below ground. On the first lower level is an exhibition of Polish art from the 19th century onwards, including a large portrait by the artist Jan Matejko, whose former residence and studio I had visited in Kraków. On the level below is the main exhibition space telling the history of Upper Silesia from earliest times to the rise of Solidarity.

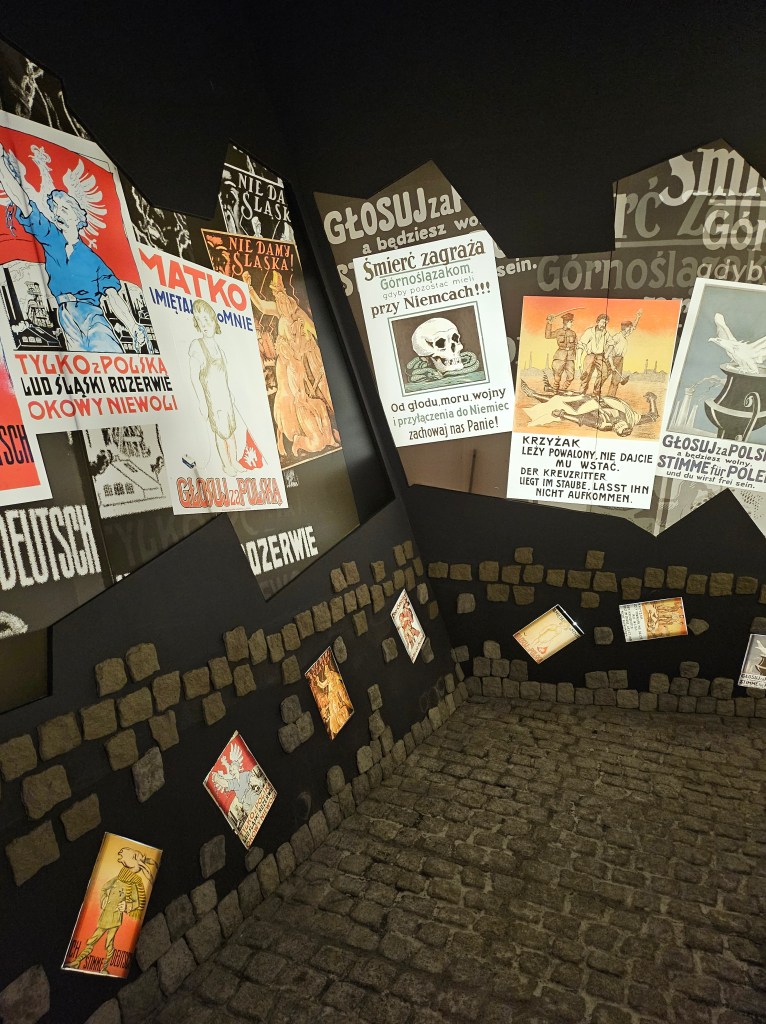

The history of Upper Silesia is complex with its territory swapping between Poland and Bohemia in the early Middle Ages, before being conquered by Hungary and becoming part of the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1526. In 1742 much of the area was captured from Austria by Prussia, with just a small area retained by the Austrian province of Bohemia. In the 19th century, coal and iron ore were discovered and the area rapidly industrialised, with Prussian Upper Silesia becoming part of Germany in 1871. Following World War I there was a plebiscite to determine the fate of German Upper Silesia, which resulted in the area being split between Poland and Germany. However, the boundary was in dispute and was eventually settled following the three Silesian Uprisings by the Poles against the Germans in the early 1920s. Katowice (Kattowitz in German) was a majority German town, but because its votes in the plebiscite were amalgamated with those of the surrounding area, it became part of Poland. Austrian Silesia became part of the new Czechoslovakia. During World War II, Upper Silesia was incorporated into the Third Reich, becoming a major production centre for the war effort. After World War II all of the former German Upper Silesia became part of Poland, as the Polish borders shifted westwards. However, the former Austrian Silesia remained in Czechoslovakia.

The exhibition was fascinating and detailed and we spent nearly three and a half hours there. At the time of our visit there was just one other building on the site that you could go in, the former baths, which was hosting a temporary exhibition of modern art and posters.

We eventually dragged ourselves away to walk a short distance to our hotel. We just had time to settle in before heading out to the restaurant in the city centre we had booked for dinner that evening. There I started with duck pierogi, followed by beef roulade.

After dinner we went for a brief explore of the city centre, including visiting the Christmas Market in the Rynek. As Katowice is a modern city, being little more than a village in the 19th century and also heavily bombed in World War II, it was noticeable that the city centre contains virtually no old buildings. By now it was bitterly cold, several degrees below freezing, so once we left the Christmas Market we walked briskly back to our hotel.

Day 2 – Saturday 29th November 2025 – Katowice to Ostrava

We made our way through the still frozen streets of Katowice to reach the Museum of Katowice History for when it opened at 10am. We were greeted by friendly staff, one of whom escorted us up to the first floor. Here there are two apartments furnished as they would have been at the start of the 20th century. One was for a very affluent upper-middle class family and the other for a middle class family of more modest means.

On the third floor is the permanent exhibition on the history of the city. This overlapped a little with the history that we had learnt from the Museum of Silesia the previous day, but largely complemented it. Prior to its rapid industrialisation in the mid 19th century, Katowice (or Kattowitz as it was then known) was little more than a village, which explains why there is no historic old town. The development of mines and heavy industry caused Katowice and the surrounding villages to grow rapidly in size to form the massive conurbation that surrounds Katowice today. After nearly two and a half hours in the museum we had to tear ourselves away in order to catch our bus, leaving no time to visit the museum’s special exhibition on Haute Couture. I guess we like to do museums more thoroughly than the average visitor, as one review of it that I read suggested that it would take no more than 10 minutes to see.

A brisk walk through the city centre brought us to Katowice bus station, a little to the west of the railway station. While there are trains from Katowice to Ostrava, at the time that we wished to travel it was more convenient and quicker to go by bus. The bus that we were catching was a Warsaw to Vienna service and it pulled into the bus station on time at about 1pm. It called at a couple of small towns in Poland before crossing into the Czech Republic. As we had a pre-booked guided tour arranged in Ostrava, it would have been very inconvenient if the bus were to be much more than 30 minutes late. I noticed that it initially did not follow the direct advertised route to its first stop, but rather took two sides of a triangle by motorway to get there. This meant it lost 10 minutes against its schedule, time it did not recover before Ostrava. There was no sign of any infrastructure for border checks, other than a small empty lay-by, as we crossed imperceptibly from Poland to the Czech Republic on the motorway.

We arrived at Ostrava bus station at 3pm, and I decided that we should have time to go by bus to check into our hotel and leave our bags before proceeding to our tour of the Villa Grossmann at 4pm. However, because of roadworks affecting the road junction next to the bus station, there was no sign of the bus stop from where Google Maps was suggesting we catch a bus to our hotel. I hastily downloaded the Ostrava public transport app to get an up to date bus route map to find where the trolleybus we needed was now starting. I had visited Ostrava once before, on my Chess Train journey in 2018, and we were staying in the same hotel. A slightly slow hotel check-in and the delay in finding the right bus stop meant that we were rather tight for time, particularly when the bus to the Villa Grossmann was a few minutes late.

We arrived at the Villa Grossmann just in time for our tour at 4pm. There were four other people on the tour, which was conducted in Czech, but we were given information sheets in English describing each of the the rooms on our tour. The Villa was built between 1922 and 1924 by František Grossmann. a German speaking architect and builder, in a highly decorative style. It was built to be his own private home. Despite being one of the richest families in Ostrava, the Great Depression took its toll on their finances and in 1932 Grossman and his wife committed suicide and the Villa was sold as part of bankruptcy proceedings. Eventually in the 1960s the Villa was acquired by the city council which first used it as school and then as a kindergarten. The building became increasingly dilapidated and the kindergarten closed in 2005. After a restoration to its former glory which took two years, it was opened to visitors in 2024. The tour was informative, taking us from the basement boiler controlling the hot air central heating up to the spartan attic. In between, the main floors of the villa are very ornate and the restoration has been immaculately done.

That evening we ate in a restaurant about a 15 minute walk away from the city centre, getting there by going past Ostrava New Town Hall, which was illuminated with Christmas lights. The restaurant we chose had lovely food, although the waiters spoke little English and the menu was only in Czech. I had chicken liver pate to start, followed by pork served with grilled vegetables on a bed of puréed cauliflower flavoured with saffron. To drink, I started with an unfiltered Moravian lager followed by a deliciously smoky dark porter.

After dinner, we went back into the centre to wander through the old town. The Christmas Market in Masaryk Square was starting to pack-up for the evening. From there we walked to the brightly lit opera house (the Antonín Dvořák Theatre), where we would be going the next day.

Day 3 – Sunday 30th November 2025 – Ostrava

Although it was slightly misty when we awoke, the weather forecast suggested that it was likely to get worse as the day progressed, so we decided to go up the tower of Ostrava New Town Hall, which opened at 9am, an hour before the other attractions in the city. The first challenge was finding the way in. After walking all round the building looking for an entrance to the tower, we concluded that one needed to go through the main doors of the Town Hall. This was indeed the case and within the main foyer of the Town Hall there is a lift which you take to the sixth floor. This brings you to a small information centre and ticket office for the tower. From here you get a different lift to take you to the top of the tower. It was cold at the top and the views were not great – we could barely make out the centre of of Ostrava, a few hundred metres away. We could just see across the Ostravice river, which used to form the boundary between Silesia and Moravia. The far bank is in Silesian Ostrava, which was a separate city until the 20th century, while the current historic centre was in Moravian Ostrava.

We next went to the Ostrava City Museum, situated in the Old Town Hall on Masaryk Square, arriving shortly after it opened at 10am. I had visited this museum when I came to Ostrava on the Chess Train in 2018. I was disappointed to discover that the exhibit devoted to the famous 1923 Chess Tournament in Ostrava, featuring many of the leading players from the golden age of chess, which I had seen in 2018, was no longer on display. The ground floor and basement told about the archaeological excavation of the houses that once lined the street behind the museum. The first floor was devoted to telling the history of Ostrava. Like Katowice, Ostrava had rapidly industrialised in the 19th century with the discovery of coal and iron ore. Numerous coal mines were opened all over the city and there was a massive iron works just to the south of the city centre. The second floor had a special exhibition on the cafés of Ostrava, as well as the permanent exhibitions on the geology and wildlife of the surrounding area. The top floor also had a special exhibition on Freemasonry in the city, which now seems to have been revived after being suppressed during Nazi and Communist times.

We eventually dragged ourselves away after nearly three hours in the City Museum and set off to walk the short distance to the Silesian Ostrava Castle across the Ostravice river from the city centre. Unfortunately, we discovered that the footbridge that we had intended to use to cross the river was closed and to walk to the castle would require a long detour along a busy dual carriageway. However there is a tram line which crosses the Ostravice on its own bridge across the river. We caught the tram for a couple of stops to get to the castle. Here the snow still lay thicker on the ground than it did in the city centre. The Silesian Ostrava Castle was originally built in the 13th century as a defensive fortification of the boundary of Silesia, but the current structure has been extensively rebuilt after some of the castle was illegally demolished in the 1970s. There was an art exhibition in the tower of the castle, but at the top there were no windows to give you views. Most of the parts of the castle that you could wander around were exposed, so it was quite cold on a winter afternoon. However, in the castle cellar, there was a small exhibition about its history, with most of the information being only in Czech.

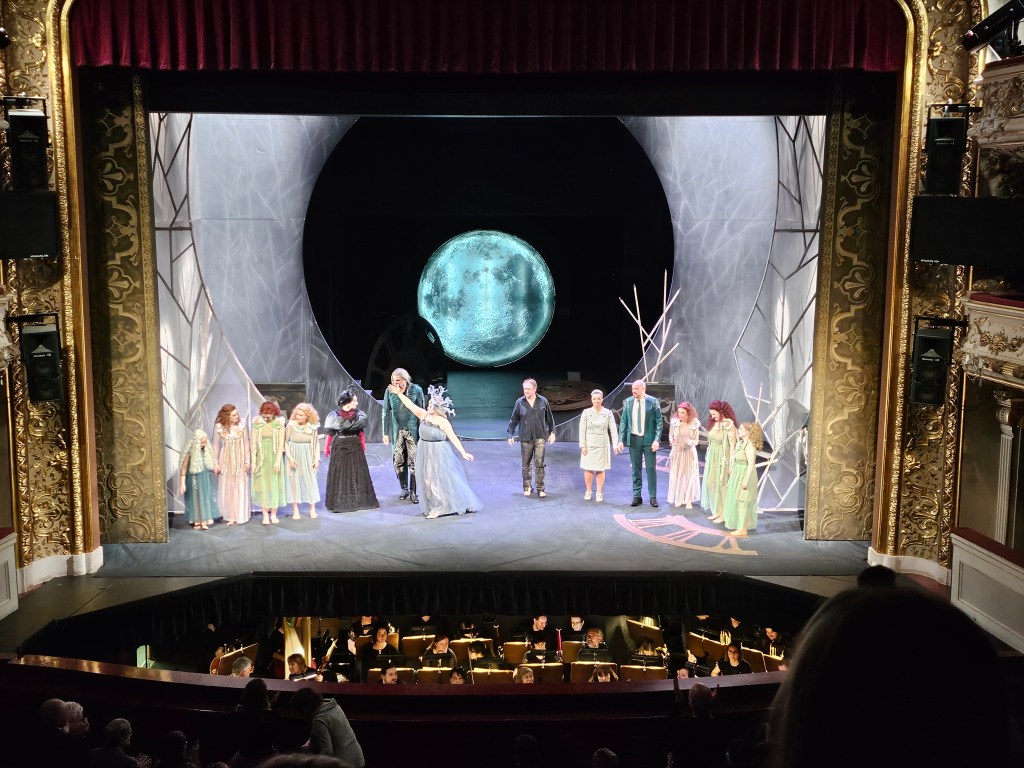

As the Silesian Ostrava Castle had taken less time than we anticipated, we were able to take a tram back to our hotel to warm up with a cup of tea before getting ready to go to the opera. We were attending a matinee performance of Dvořák’s opera Rusalka, starting at 4pm. I was slightly nervous about what to expect, as the tickets had been ridiculously cheap, even for some of the best seats in the house. The performance had sold out and there was a steady stream of people going into the Antonín Dvořák Theatre when we arrived. The theatre was first opened in 1907, but has been extensively reconstructed on a number of occasions. The interior is lavishly decorated with an ornate painted ceiling and massive chandelier in the main auditorium. We had seats in the centre of the second row of the first balcony and I was pleased that they had a generous legroom, something that is sometimes lacking in older theatres. The theatre is quite intimate, holding just 500 people and the stage is narrower than in other opera houses I have been to. I needn’t have worried about the quality of the production, both my son and I thought Rusalka was superb and we enjoyed it very much. The performance had two intervals and we left at just after 7:30pm, which seemed much later than it was.

On the way back from the opera house we found a pizza restaurant in which to eat. I accompanied my pizza with some locally brewed beer.

Day 4 – Monday 1st December 2025 – Ostrava to London

We caught a bus and then a tram to take us to the Dolni Vitkovice area, south of the city centre. Here there is a sprawling former industrial complex, consisting of coal mines, coking ovens, and iron and steel works, which finally closed down in 1998. Parts of the site has now been turned into a museum and cultural area, but being a Monday many of the attractions were shut.

We had booked ourselves onto a tour of the former iron works commencing at 10 am. We were joined by four other participants on the tour and a tour guide who spoke no English, so we were given information sheets explaining about all the places that we would be seeing. Before we could start the entire group had to don hard hats – these were colour coded (ours were green), presumably to distinguish between different groups at busy times when there may be more than one group touring the site. We went via some coking ovens to the Bolt Tower, a large structure which used to house a blast furnace, into which the raw materials were dropped from a great height. We had to climb to the top of Bolt Tower, as the lift was out of order. On our descent we went into the heart of the blast furnace and then to the outside of it to see where the molten pig iron was tapped and the slag siphoned off. The final point of the tour was to visit the control room for the whole site, which contained what was then state of the art electronic equipment when the site closed in 1998. There is still a 1998 calendar on the wall of the control room.

The only museum in the Dolni Vitkovice site that is open on Mondays is a branch of the National Museum of Agriculture. I had enjoyed visiting the National Museum of Agriculture in Prague a few years previously, so we decided to visit the Ostrava branch, when our guided tour was over. The Ostrava museum specialises in displays of agricultural machinery and the properties of food. Although quite interesting, it only took about an hour to look round the whole museum, so we had finished by about 1pm. We went back to the Dolni Vitkovice information centre, where we had started our tour earlier that morning, as it had a cafe, where we stopped for some lunch.

After lunch we returned to the city centre and did a bit of shopping in the Christmas Market. We tried to visit a couple of nearby churches, but they were both locked. Since we had a little time to kill, we decided to go for a ride on the big wheel which had been erected in Masaryk Square alongside the Christmas Market. Our fare got us three complete spins on the wheel, I suspect at busier times you would not go round as much, and you would be starting and stopping more often to let other people get on and off.

It was then time to head for the airport. Our flight back to London was due to depart at 17:35. It was one of only two scheduled passenger flights from Ostrava that day, the other being at 05:30 in the morning to Warsaw. The airport bus only runs once to connect with each flight, the timetable varying day by day. The airport is 26km from the centre of Ostrava and the bus departs from the terminus of the tram line in the south of the city. We got to this terminus in plenty of time, so to keep warm we visited a nearby supermarket to do some more shopping. When we returned to the bus stop, the bus was waiting and departed promptly. There was only one other passenger on the bus, so we assumed (incorrectly, as it turned out) that our flight would be lightly loaded.

The incoming flight arrived early and parked alongside the terminal building, so that no tug would be required to push it back from the stand. As soon as the last of the incoming passengers had got off we were allowed to board and I was hopeful of a prompt departure. However, by now the airport was enveloped in freezing fog, conditions that until a few years ago would have prevented any flights from landing. The captain announced that because of the temperature, the plane would need to be de-iced before it could take off. A de-icing truck came alongside the aircraft and spent about 10 minutes de-icing each wing in turn. We then taxied to the runway, which because of the fog you could not see along its whole length. The plane sat at the end of the runway for a couple of minutes revving its engines far more than I have ever experienced previously, before suddenly hurtling down the runway at high speed. These various operations delayed our departure by 30 minutes. We made up some of this time on the way back to London and landed at Stansted Airport just 10 minutes late.

My son and I thoroughly enjoyed Rusalka and thought that the Ostrava Opera House was well worth visiting. As well as Rusalka, my son had mentioned to me another rarely performed opera that he would like to see and I had been trying to find out if any opera company was putting it on its repertoire for 2026. By a total coincidence, after we had arranged to see Rusalka we discovered that the other opera he wants to see will also be staged in Ostrava next summer. So I think a return trip is highly likely.