“À la recherche du temps perdu“ (Marcel Proust)

This trip was designed to combine a visit to a country I last went to a long time ago with a visit to a country that I had never been to before. In 1983, I undertook an Interrail journey across Europe and back. My time in Romania had been memorable, as it coincided with a dark period in Romania’s history – the economy was starting to fail and Ceaușescu’s response was to impose austerity, which led to rationing and food shortages. I previously told of my time in Romania in 1983 in an earlier post on this blog. I was intrigued to see how the country had changed in the intervening 41 years, and I tried to design an itinerary that closely followed the route I travelled back then.

Day 1 – Tuesday 8th October 2024 – London to Cluj

As my flight to Cluj was departing from Stansted Airport at 10:55, it required an early, but not ridiculously early, start from home. Although a number of departures from the airport were delayed that morning, mine was running on time. To minimise the time standing in the queue to board the aircraft, I usually aim to pass through the departure gate after most other people have gone through. However, I noticed something a bit odd that morning. There was never a long queue of people waiting to show their boarding cards. The reason became apparent when I was on the plane – it was only about a quarter full and I was the only person occupying my block of seats, the most lightly loaded flight that I have been on in a long time. Also, listening to those who were on the plane, I think that I may have been the only non-Romanian passenger.

The flight departed just a few minutes late and arrived in Cluj at about 15:45. We had to wait for everybody to get on board a couple of buses to take us to the non-Schengen arrivals area. Romania has this year joined the Schengen area for air travel, but not for land crossings. It did not take long for everyone to get on the buses, which deposited us at a side building where the passport control was housed. As I had positioned myself by the bus door, I was one of the first people to go through the passport area and so did not have to queue. In researching how to get to Cluj city centre, I had contradictory information. The airport said that there was an airport express bus that ran every ten minutes, but the regular trolley-bus services which went from the main road by the airport were suspended due to roadworks. However, Cluj transport authority’s website implied the airport express bus only ran hourly (on the hour from the airport), but that only one of the trolley-bus services was suspended, the other was running every 10 – 15 minutes. I emerged from the terminal just before 4pm to see the airport express bus waiting there, so I jumped on it just before it departed promptly at 4pm. It would seem that the airport’s website information was wrong, and I had been very lucky with the timing of my arrival.

It took about 30 minutes to reach the centre of Cluj, as the road into the city was clogged with traffic. I got off a stop before the terminus, since I had correctly guessed that it would be quicker to walk the last part. I checked into my hotel, where I was given a slightly odd ground floor room, the door of which was in an open air courtyard, which served as the outdoor seating for a restaurant. This had the disadvantage that, if I kept my window open, both noise and smoke drifted in from outside. Also, while the window had curtains, the slightly frosted glass door to the room did not. Inside the room there was a poster (in Romanian) advising what do to do in the event of an earthquake – unfortunately, my room did not contain a table under which I was supposed to shelter during an earthquake.

I judged that I would not have sufficient time to visit any of the many museums in Cluj. (Cluj’s official name was changed to Cluj-Napoca during Communist times; Napoca being the name of the Roman settlement. Although official references still use Cluj-Napoca, it is generally referred to as just Cluj.) Ideally, I would have scheduled more time in Cluj, but I could not get the rest of my schedule to work, without skipping somewhere else I wanted to visit. So I just went to the Tourist Information Office to pick up a map to enable me to devise my own walking tour of the main sights in the city. This took me past both the Catholic and Romanian Orthodox cathedrals. Cluj has a significant Hungarian minority, although numbers declined in the 1990s following the election of a Romanian nationalist mayor. A number of buildings I saw on my walk had Hungarian signs, including a Hungarian theatre. I was also pleased to find a street named after the 19th century Hungarian mathematician János Bolyai, who had been born in Cluj (or rather in Kolozsvár as it was known in Hungarian at the time).

A feature of my visit to Romania in 1983 had been the difficulty of finding places to eat, particularly in Transylvania (Cluj is the largest city in Transylvania). In researching where to eat that night, I was pleased to discover an abundance of well reviewed restaurants, which seemed to have very modest prices. I chose one a short walk from where I was staying. I started with hummus and caramelised onion and followed this with a pork chop with mashed potato. To drink, I had a wheat beer, and then tried a glass of the local red wine.

Day 2 – Wednesday 9th October 2024 – Cluj to Sighișoara

I knew that I would not be able to do justice to Cluj in the brief time that I was able to spend there and so it was with a heavy heart that I walked to the station, but consoled myself by thinking that Cluj could be the starting point for a different future itinerary.

Before I left my hotel, I had seen that my train was running 20 minutes late, but that it had a 20 minute wait scheduled at Cluj to allow it to change direction, so I hoped that it might make up some of this lost time. In the event, it still took 15 minutes to bring the locomotive to the other end of the train, so it left about 15 minutes late at 10:30. I was travelling in the one first class carriage on the train, which was largely empty, apart from a French couple with an enormous amount of luggage who were occupying the pair of seats in front of mine.

Throughout the initial part of the journey the train did not exceed 30 mph as it travelled through the empty landscapes of northern Romania, and started to lose more time. When the train reached the vicinity of Blaj, the track improved and it clawed back some of the lost time, only to lose it again in the approach to Sighișoara, where it arrived 26 minutes late at 14:15.

In 1983, when I arrived in Sighișoara, it was early on a misty morning and I recall not being totally sure that I had reached Sighișoara, as there were no signs on the platforms. In this regard, nothing had changed, but now with the benefit of GPS available on your phone, you at least know where you are. Sighișoara station did not seem to have changed much in the intervening 41 years and was possibly now even more dilapidated.

The station is a little way from the old centre of Sighișoara, across the Târnava Mare river. On the way, I passed a Soviet war cemetery, which was surprisingly well maintained with a couple of freshly laid wreaths. Only the main grave in the centre had a name on it, the rest were for unknown soldiers. One account that I read suggested that by the time the Soviet army had reached Sighișoara, the Germans had already fled and that the Major honoured in the main grave was shot by a local when he was trying to rape his wife. The unknown soldiers met their fate by being drowned in a drunken stupor, when a wine storage tank they had shot holes in to access the wine had burst open, flooding the cellar they were in. I cannot verify the veracity of this, but I do not think I have previously encountered such a pristine Soviet memorial in Eastern Europe in recent times.

I crossed over the river by a footbridge near the Romanian Orthodox Cathedral and began to zig-zag up a steep path to enter the heart of Sighișoara within the city walls. I recall in 1983 that entering within the city walls was like stepping back in time – there were no people about and very few shops (which had nothing in them, other than pictures of Nicolae Ceaușescu). Now, while the architecture was unchanged, there were a number of obvious tourists wandering around, and the shops were much more garish and obviously targeted at the tourist market by exploiting Sighișoara’s Dracula connection.

Sighișoara’s city museum is located within the old Clock Tower and as it shuts at 3:30pm, I went straight there to give me time to view it before it closed. The exhibits, including a scale model of the town, are laid out on the different floors within the tower, but the collection is not large and I need not have worried about not being able to see it all before it closed. There is a viewing platform at the top of the tower, but at the time of my visit it was closed as workmen were undertaking repairs. However, looking through the photographs I took in 1983, I worked out a couple of them must have been taken from the top of the tower, although I had no recollection of having been there previously.

As there aren’t very many hotels in the old part of Sighișoara within the city walls, I had booked a room in some privately run apartments right in the centre of the medieval town. That morning I had received an e-mail from the owners confirming that I had booked a double room for the night, giving me a code to enter the courtyard and also to enter my room. As this was very close to the Clock Tower, I thought that I would call in to drop off my bag before exploring further. I had no difficulty accessing the courtyard, from where I discovered that there were a number of rooms on two levels. My problem was that about five of them were labelled double rooms and I had no information to tell me which one was supposed to be mine. So I started trying to use the key code on each of them in turn without success. At that point I tried phoning the number that I had been given, but the call cut off without connecting. When I tried going round the rooms again, my multiple failed attempts set off an alarm. At this point, I was about to give up and come back later when the owners arrived. They confirmed which room was mine – I had tried it before, but obviously must have made an error entering the code for this room. The couple who owned the apartments were very friendly and insisted that I help them drink a bottle of home made schnapps.

Having extricated myself from a mid-afternoon drinking session, I climbed up the hill in Sighișoara to visit the place that had made a lasting impression on me from my 1983 visit. On that occasion when I had first arrived it was early in the morning, with nobody around and the town shrouded in mist. As I climbed up to the Church on the Hill, there were sheep grazing outside and I could hear organ music playing inside, but when I tried to go into the church the door was locked. Forty one years later it was a warm sunny afternoon and there were no longer any sheep to be seen. However, this time the church was open and I went in. I was met by a friendly man who looked after the church and he offered to tell me a little about its history. He was fascinated to learn that I had visited in 1983 and wanted copies of the photographs that I had taken then. He had had lived in Sighișoara all his life and was six years old in 1983. We reminisced about the paucity and poor quality of food, and he said that that he was taught in primary school that if any foreigner should talk to you, you had to go to the police station immediately to report the conversation. He was an attendee at the church back then and told me the organist who I had heard was still alive, although no longer playing the organ. However, he was puzzled as to why I had heard organ music on a Wednesday morning, as the services were only held on Sundays.

What I had not realised at the time of my previous visit was that Sighișoara was a centre for the German-speaking Transylvanian Saxons. During and immediately after the Second World War, the Transylvanian Saxon population in Romania was reduced by more than half to number about 100,000. But after the fall of Communism more than 90% of the remaining population left – helped by having an automatic right to German citizenship. The Church on the Hill is the Transylvanian Saxon church in Sighișoara and the adjoining building was the German School. In the interior of the church the memorials are all written in German, and a number of them have been brought from other Transylvanian Saxon churches in the region to preserve them following the departure of their parishioners.

Behind the church on the other side of the hill from the town is a large Saxon cemetery, with all the tombstones written in German and commemorating the deceased who all had very Germanic names. In wandering around this graveyard, I may have solved the puzzle of why the organ was being played early on a Wednesday morning. I found a tombstone to someone who had died just five days before my visit in 1983. Perhaps the organist was practising for the funeral to be held later that day. As I walked back down the hill to the town using the covered steps, I felt quite emotional.

A feature of Sighișoara is the large number of fortified towers that ring the old town, some of which are now just private residences. I paid a visit to another one, the Blacksmiths Tower, which contains a small museum. With the viewing gallery of the Clock Tower having been closed, I had hoped to get good views across the town from the Blacksmiths Tower, but it does not have any windows facing that direction. For the remainder of the afternoon I constructed a walk based on a map that I obtained from the tourist office taking me to the other parts of the town within the walls that I had not yet visited, rewarding myself with a pineapple ice cream as I wandered.

As rain was threatening that evening, I went to a restaurant near where I was staying at which I dined on beef goulash, followed by a selection of cheeses.

Day 3 – Thursday 10th October 2024 – Sighișoara to Brașov

When I left my apartment that morning, Sighișoara was again shrouded in mist, as it had been when I first arrived 41 years previously – the Church on the Hill was barely visible from the centre of the old town. Before setting off, I checked how my train was running and found that it was about 50 minutes late. The train was the Dacia conveying through carriages from Vienna to Bucharest and its delay had already been incurred by the time the train had entered Romania. So I did not rush to the station, as there would have been little point in arriving early. At Sighișoara station, I was surprised that there were no departure boards, neither in the station building nor on the platforms and the only timetable on display was out of date and incorrect. Consequently, there was nothing at the station to tell how late the train was running nor from which platform it departed.

The train had made up some time on the approach to Sighișoara and eventually rolled in 35 minutes late at about 09:55. There were no first class carriages on this train, but my reserved seat was in a compartment which I had entirely to myself throughout the journey to Brașov. I had thought that the previous day’s journey was slow, but this one was even slower – for much of the time it trundled though the scenic foothills of the Carpathian mountains at 15 mph. During most of the journey we were in sight of a new line that was being built, which cut a few corners compared with the current meandering line – so hopefully within a few years journey times will be much improved. We were further delayed by engineering work just outside Brașov, eventually arriving 45 minutes late at about 13:20.

Brașov station is over two miles away from from the historic centre of the city, where my hotel and other attractions are located. Looking back, I am amazed how I found my way around in 1983, as I recall there was no tourist office at the station. Of course, these days you just open your phone and let Google plot you a route. My phone informed me that there was a bus going from the station to where I wanted to go and that it should be possible to pay the bus fare by tapping my credit card on a reader on the bus (as I had done for the bus ride from the airport to the centre of Cluj). I needed a number 4 bus and I saw one pulling into the bus station as I approached, which I hopped on via the rear doors. The bus was full and I declined the offer of a seat from a young woman. When I tried to tap my card on the reader, nothing happened, despite me following the instructions on a poster (in Romanian) on the bus window. I’m not sure if the reader was faulty, but I had a free ride into Brașov.

First of all, I called into the hotel I had booked to drop off my bag. As in Cluj, my room was on the ground floor, off an open air courtyard – but, thankfully, unlike in Cluj, there were no tables immediately outside my bedroom window.

I then walked across the main square in the centre of the old town to reach the edge of the built up area from where the cable car started to go up Tampa mountain. One immediately noticeable difference from 1983 is that there is now a giant set of letters at the top of the mountain spelling out the name of Brașov, which can be seen from all over the city and which are illuminated at night. I chose only to buy a one-way ticket for the cable car, even though return tickets are priced at only a small premium compared to the single fare. In 1983, I had ridden up on the cable car when it had first opened for the morning and I was the only passenger, other than a crate of fish for the restaurant at the summit. This time there was a queue of people waiting to get on and the car I went on was full – also a cable car attendant travelled with the passengers, which did not happen in 1983.

At the top I walked along the summit ridge to peer out through the large letters spelling out Brașov’s name. I then followed a marked walking trail (the same one as I think I walked down 41 years earlier) to return to the city. I am relatively slow going downhill on uneven terrain and it took over an hour to walk down the zig-zagging path through the densely wooded hillside. I rewarded myself with a strawberry sorbet on my return.

I realised that I would not have time to visit more than one of the many museums in Brașov, so I chose to go to the Museum of the Urban History of Brașov. This was quite interesting, but a bit smaller than I was anticipating. That gave me time to visit the nearby Black Church (Biserica Neagră), so called because of the discolouration of its stonework, possibly due to a fire which engulfed the city in 1689. The church, cathedral like in size, is a Lutheran church of the Transylvanian Saxon community, with most of its memorials being written in German.

To finish off my day I went for a walk round the rest of the old city centre, keeping an eye out for a suitable restaurant in which to eat that evening. When I did go for dinner, I dined on Bulz with smoked sausage, a traditional Romanian dish of baked polenta and cheese. For dessert, I chose plum dumplings, which were a little too sweet for my taste.

Day 4 – Friday 11th October 2024 – Brașov to Bucharest

Given my difficulty in paying for my bus fare from Brașov station the previous day, and as the weather was good, I decided to walk back to station. For the first time on this trip I was having a hotel breakfast and I got to the dining room when it opened, only to find a large group of Chinese tourists also waiting to go in. I don’t eat big breakfasts, but the Chinese group was hoovering up much of the available food, which is presumably why I normally don’t find paying separately for breakfast a good deal.

I had realised the previous night that the train I was catching that morning was also going to be a cross-border one, this time the Ister, which had started in Budapest. Given the delay to the Dacia the previous day, I contemplated whether it would be worthwhile changing my booking to an alternative Brașov to Bucharest service, which would be starting in Brașov and leaving only ten minutes later. However, when I woke up and checked how the trains were running, I was pleasantly relieved to see that the Ister was on time.

I arrived at Brașov station in good time for the 09:02 departure and it did indeed roll into the station on schedule, 10 minutes before it was due to depart. In complete contrast to the Dacia the day before, every seat in my carriage was occupied on departure from Brașov. The journey south through the Carpathian mountains was very scenic, but I was sitting on the wrong side to get the best views and, because the train was full, there was no opportunity to swap seats. The train kept more or less to time throughout most of its journey, but there were some delays on the final leg after leaving Ploiești, which meant that it arrived at Bucharest Nord ten minutes late at 11:40.

Bucharest Nord station did not seem to have changed much in the 41 years since I was last there, other than some of the food outlets now belonging to the usual ubiquitous global chains. Although I had had booked my train ticket to Bulgaria on-line in advance, unlike the tickets within Romania, I had to pick-up a physical ticket at Bucharest Nord station. The advice is not to leave picking up your ticket until the last minute, so I decided to do so when I first arrived. In the large booking office, there is only one window than can dispense international tickets and when I got to it there was a queue of about eight people waiting. The queue moved very slowly, with the man at the head of the queue when I arrived undertaking a seemingly interminable transaction. It did not help that some people then jumped the queue, claiming that that they had been told earlier to come back at a specific time. When I finally reached the front 45 minutes later, my tickets were dispensed in under two minutes. My next task while at Bucharest Nord was to acquire a reloadable card for use on Bucharest’s public transport.

It is only possible to visit the Palace of the Parliament, the monstrous building commissioned by Ceaușescu but unfinished at the time of his execution, by pre-booked guided tour. These are made available for phone booking the day before, but any unsold tickets can be obtained at the venue. After dropping my bag at my hotel I went straight to the Palace of the Parliament, but there were no longer any tickets available for tours on Friday or Saturday. So I could only look at the building from the outside – it is one of the largest buildings in the world and whole neighbourhoods were demolished to enable its construction.

I next went to the National Museum of Romanian History, which I had visited in 1983, when it had extensive displays of personal knick-knacks acquired by Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu. The building containing the museum has been undergoing renovation for the past 20 years, meaning that only the ground floor is accessible. Consequently, this area is largely used to showcase, on a rotating basis, just some of the museum’s collection. The Ceaușescu memorabilia had gone, but there was now far more about the former Romanian monarchy than I recall from last time.

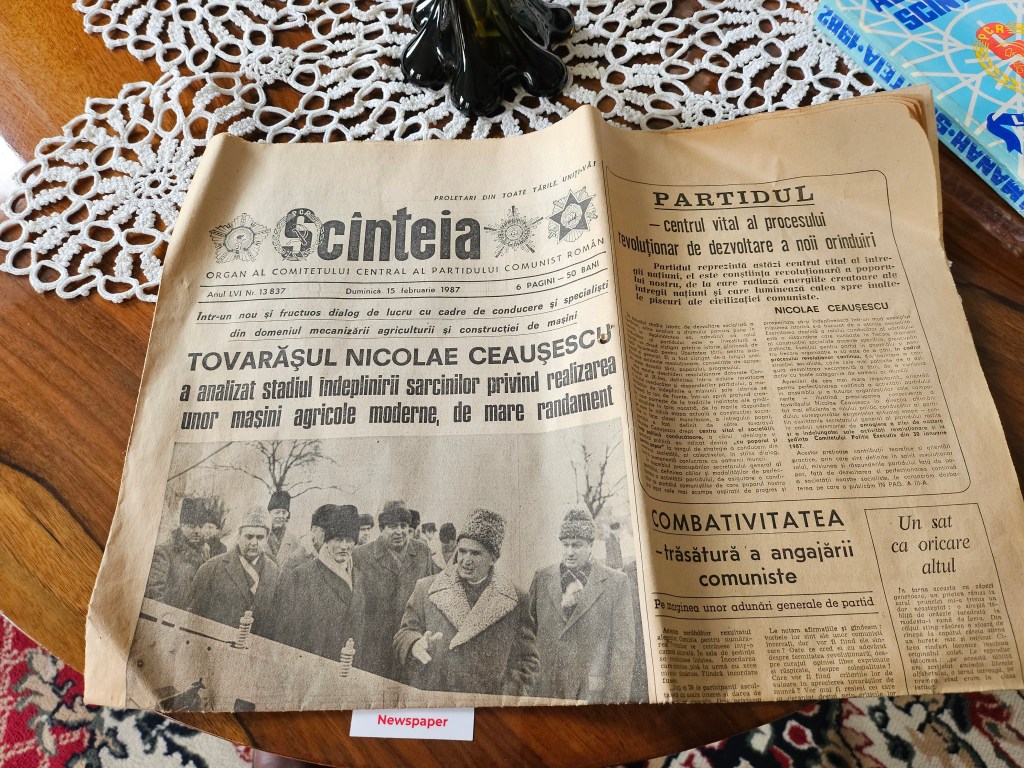

Next stop was the Museum of Communism, which although quite compact, squeezed in a lot of information and I thought it was very well presented, with helpful staff to answer your questions. I particularly liked that they had a selection of communist era newspapers that you were allowed to flick through – reminding me that during my previous time in the country the only photograph on the front page each day was one of Ceaușescu.

I then took a circuitous walk back to my hotel taking in some the other sights of central Bucharest. I walked through what is now Revolution Square (previously Palace Square), looking up at the balcony of the former Communist Party headquarters from which Nicolae Ceaușescu tried to deliver a speech on 21 December 1989 when the crowd started booing and the live TV feed was cut. On the following day, the Ceaușescus escaped from the roof by helicopter when the crowd stormed the building and just three days later the Ceaușescus were summarily tried and executed. I then walked past the nearby Athene Palace hotel, where on the opposite corner I recall sitting in bar on my final evening in Romania in 1983 – just six years later this area was the location of some of the bloodiest fighting of the Romanian revolution.

I had an early dinner near my hotel in a small establishment specialising in burgers, before proceeding to the Bucharest Opera House, a ten minute walk away. Before I departed on this trip, I noticed that they were staging Nabucco on this particular evening and I had booked a ticket. Although I had seen Nabucco in Gothenburg the previous year, I thought it would be interesting to visit an older Opera House and to see Nabucco staged in a traditional setting, rather than the modern interpretation that I had seen in Gothenburg.

The first thing I noticed was that the Bucharest audience had dressed up far more than in Gothenburg. Some of the men were in dinner jackets and most of the rest in suits, while most of the women were wearing slinky evening dresses. Although the Bucharest Opera house looks old, it was only built in 1953. Nonetheless, I discovered that the legroom provided in the seats was not generous, in line with what you might expect from an older building. The performance was enjoyable, but I did not feel that it met the standards I had experienced in Gothenburg. In particular, the acting was rather wooden – so although the singing was fine, there was not the emotional intensity that the Gothenburg production had. I also found rather irritating the audience’s desire to applaud at the end of every famous aria or chorus, which rather broke up the flow of the opera.

Day 5 – Saturday 12th October 2024 – Bucharest

While still at home I had booked a guided tour of the Primăverii Palace, the former private residence of Nicolae Ceaușescu. It is located in the Primăverii district a couple of miles north of the city centre. I was originally going to catch a bus there, but given there were a number of road closures that morning for a 10km road race being held the day before the Bucharest marathon, I was worried that the buses might not be running to schedule. Instead, as the forecast rain had not yet arrived, I decided to walk there following the wide boulevard I remembered having walked down in 1983 on my way to the Herăstrău Park. On that occasion I remember being passed by a high speed motorcade with motorcycle outriders – given the location, quite probably it was one of the Ceaușescus (or one of their circle) going back to the Primăverii Palace.

When I arrived at the building a few minutes before the 10:15 tour was to start, I was asked to wait outside until the due time. It was a good job I had booked in advance, as there was a notice at the entrance saying that all tours that weekend had sold out. At 10:15 the waiting group was instructed to don plastic coverings for our shoes and we were ushered inside. It was explained that we would be seeing about 50 of the 173 rooms in the building, the remainder are still used by the Romanian security services who control the building. The security services had recently decreed that no internal photography was allowed, which was a shame. Our guide delivered his talk in a monotone voice, ending his description of each area with the statement “you may now proceed with care to the next room”.

This was very much the private residence of the Ceaușescus and was not used for any official receptions. It was the home, albeit owned by the Romanian state, of Nicolae and Eleana Ceaușescu and their three children. They moved in when Ceaușescu replaced Gheorghiu-Dej, who had lived there previously, as General Secretary of the Communist Party. The private rooms are still furnished as they were at the time Ceaușescu was deposed. There are separate suites of rooms for each family member, as well as a joint living room and dining room. All are opulently furnished, often with gifts provided from foreign heads of state, such as a Brussels tapestry which adorns one of the walls. The overall impression is that everything is rather over the top, with no real sense of style dictating how it is furnished. Dotted around various rooms were a number of chess sets, and an early British-made chess computer, as Ceaușescu was a keen player. The building also contains a sauna and swimming pool, which is surrounded by a colourful mosaic. When we had visited all the rooms we were allowed to see, we exited via the garden.

From the Ceaușescu residence I walked the short distance to the King Michael I Park (formerly Herăstrău Park). Within the park is the Village Museum which I had been to during my previous visit to Romania. It has expanded slightly since then and consists of a large collection of peasant houses and other rural buildings from the different regions of Romania. Rather disappointingly, only a few of them were open for one to go inside.

When I had finished with the Village Museum, I walked through the park to a different corner from where I had come in to see Bucharest’s own Arc de Triomphe, located in the middle of a traffic clogged roundabout.

I then caught the Metro for a couple of stops from the nearby Aviatorilor station back to the centre of Bucharest. I walked past the Romanian Athenaeum, used as a concert hall, to reach the former Royal Palace.

The building of the Royal Palace is divided into four separate spaces each with their own entrance and for which one can buy separate entrance tickets. One (the gallery of European Decorative Art) was temporarily closed at the time of my visit, but I went to the other three in turn. First I went to the European Art Gallery, which houses a collection of art from across the continent, including works by El Greco, Rembrandt and Rubens. Next, I visited the lavishly ornate state rooms of the Royal Palace, including a grand staircase and painted ceilings. Finally, the biggest of the three areas was the Romanian National Gallery, which houses art from across the centuries by Romanian artists.

From the former Royal Palace I walked a few blocks to Bucharest City Museum. This is located in a rather gloomy dilapidated building, but I thought the main exhibition on the history of the city was excellent, telling a narrative story about Bucharest (and indirectly Romania) from earliest times to the present day. I found this more informative than the rather hotch-potch collection in the National Museum of History.

I then walked back to my hotel via a large city centre park with its own lake, Cismigiu Gardens. I had noticed an area of central Bucharest which was full of restaurants, but by the time I got back to my hotel I was rather tired and wanted to see if I could find anywhere more local to eat that evening. I set off to find a place for dinner about 15 minutes walk away, which had excellent reviews. The restaurant was located in a nondescript residential side street and I initially walked right past it, as there was nothing externally to distinguish it from the neighbouring houses. I was lucky to secure a table inside and had a lovely meal. I started with bread and dripping with onions, which reminded of my childhood when my mother used to make dripping. I followed it with duck served with red cabbage and mashed potato. I enjoyed the meal so much that when I left I booked a table for when I was next going to be in Bucharest on Monday evening.

Day 6 – Sunday 13th October 2024 – Bucharest to Mangalia (via Constanța)

As I had an early train to catch I went down to the breakfast room of my hotel shortly after it opened to find it surprisingly full for early on a Sunday morning. The Bucharest Marathon was taking place that day and there were a lot of nervous runners having their breakfast in my hotel. That said, a few of them did not appear to be eating particularly sensible pre-marathon food. When I left the hotel to walk to Bucharest Nord station, the police were just starting to close the nearby roads to traffic.

I arrived at Bucharest Nord in good time for my 08:20 departure to Constanța, finding it too was surprisingly busy with people waiting for trains early on a Sunday morning. I was travelling first class for the journey to Constanța and although my carriage was not full, it was much busier than on my previous first class journey of this trip. It was also the only train I caught which travelled at a reasonable speed – most of the run down to the coast was done at 80 mph and it arrived in Constanța on time at 10:47.

Constanța was a new city for me, as in 1983 I had just passed through it on a through train to Mangalia. The railway station is some distance from the historic centre of the city near the sea front. However, I broke my walk to the main part of town by calling at the Maritime Museum which was about half way. I had hoped to visit Constanța’s main historical museum, but it had closed for renovation since I originally planned this trip. The Maritime Museum traces the seafaring traditions of the area back to Roman times and describes various naval encounters in the Black Sea over the centuries. Admission to the museum was for a small fee, but I did not purchase a permit to take photos inside as its cost was four times the basic admission price. In the rear garden of the museum a number of small naval boats had been parked, which I risked photographing without a permit.

I went to the nearby Archaeological Park which contains bits of columns and other artefacts from the Roman city of Tomis, as Constanța was previously called. Also within the park was a very large communist era monument to victory.

I then carried on towards the sea front. Unfortunately, on the way I banged my knee very painfully on a bollard while hurrying to cross a road. Given I could feel it swelling up, ideally I should have found some ice to apply to it, but instead I just treated myself to a mint and chocolate ice cream to be taken internally. It was now a lovely warm day, and there were many people out strolling in the sunshine. I walked past the now closed history museum, whose building looked rather dilapidated. In the square outside the museum is a statue of the poet Ovid, who was banished to Tomis, to spend the rest of his days in exile, by the Emperor Augustus. A bit further on was a mosque, where the faithful were being called to prayer from the minaret.

I then walked past the harbour for small boats and along the seafront promenade to overlook the main industrial port of Constanța. Before returning to the station, I just sat for a while on a bench to soak up the sun.

My train to Mangalia was leaving at 14:22, and as the line beyond Constanța is not electrified it was being pulled by a diesel locomotive. Also, for the first time on this trip there were double-decker carriages, so I went upstairs for the hour-long ride along the coast. Most of the line is single track and the train reverted to the slow speeds I had become used to on Romanian railways. We went past the planetary-named resorts of Neptune, Saturn, Jupiter and Venus, which were built in the 1970s for package holidays from other communist countries and which I believe are now struggling to attract clientele.

The train arrived in Mangalia at 15:26 and I set off to walk to the hotel that I had booked. When looking for a hotel in Mangalia, I had tried to book one in approximately the same location as the hotel I had stayed in 1983. In 1983 my hotel was occupied by elderly East Germans, and I was mysteriously refused access to the the room I had originally been given because it was ‘broken’ and was moved to another – probably on Securitate orders to one where the bugging equipment worked. When I reached the hotel I had booked this time, I was fairly sure that it was next door to where I had stayed in 1983, although the facade of my 1983 hotel now seemed to have been modernised. Although I did not take a photograph of my hotel in 1983, if I lined up the end points of two piers in the distance so that their position matched that of a photograph that I had then taken looking out to sea, this only worked when I was standing outside what I believed to have been my 1983 hotel.

I checked in at my 2024 hotel and immediately went out to the beach. In 1983, I went for a swim in the Black Sea and this time I had also brought my swimming trunks along in case I wished to do so again. In the end, I decided against a swim that evening for two reasons – there was now a bit of sea breeze, so it was no longer as warm as it had been earlier and also my knee that I had banged in Constanța had swollen rather alarmingly, such that I didn’t want to do anything that would make it worse. However, I still thought that I should not come all the way to the Black Sea and not go in, so I made do with a paddle up to my calves. While trying to clean the sand off my legs an unexpected wave soaked my trousers.

After returning to my hotel to dry my trousers and remove from my body some more of the sand from the beach, I set off to explore Mangalia. By now the sun was beginning to set and the Black Sea looked very peaceful as I strolled by the marina with its moored yachts. When looking for somewhere to eat, I realised that so far on this trip I had not yet tried traditional Romanian mici, which are grilled slightly spicy sausages made from minced meat. I decided to correct this omission by going to a grill bar busy with Sunday evening customers to have mici, served with bread, chips, and mustard, washed down with a couple of beers.

Day 7 – Monday 14th October 2024 – Mangalia to Bucharest

When I awoke I was relieved to discover that the swelling on my knee had gone down and the joint had not stiffened overnight as I had feared it might. I again considered whether I should go for a swim in the Black Sea, but the weather forecast looked rather chilly for most of the morning, so I decided against it.

Mangalia was once the ancient Greek colony of Callatis and there is an Archaeological Museum displaying finds from that era. On-line information suggested that the museum was open from 9am every day of the week, which I was rather sceptical about. So, the previous evening I had gone to the museum to see if I could confirm its opening times. There was a paper notice stuck to the door saying that it was actually only open on Mondays to Fridays from 10am. This made it the only museum on these travels which was scheduled to be open on a Monday.

After further exploring of Mangalia, I went to the Callatis Archaeological Museum arriving at about ten minutes after its opening time. The door was unlocked, so I went in. However the lights were not on inside and there was nobody about. I could only look in the first room of the museum, as this was the only one to have natural light. After about 10 minutes of looking around, a cleaner arrived and turned on the lights. Only after I had finished looking round the whole museum half an hour later, did the woman who sold the entrance tickets arrive and I obtained mine as I was about to leave.

As I still had a little time to spare before my train departed, I thought I would buy a postcard to send home. While a few of the beach-side shops were open, many appeared to have closed for the season. Despite trying all the likely outlets none were selling postcards. So instead of spending my time writing a postcard, I went for a further walk round some of the parts of Mangalia that I had not yet visited.

I had booked a through ticket back to Bucharest, but outside of the summer season there are no through trains and you have to change at Constanța. I caught the 12:06 departure, which was much emptier than the train to Mangalia that I had caught on the Sunday afternoon. Although booked as a through ticket, it had given me a over an hour to make my connection in Constanța. As my train was on time, I could easily have caught an earlier departure from Constanța to Bucharest, but my ticket had a specific reserved seat for the second leg and I was unsure if one could just get on a different train. There was not time to go all the way in to the centre of Constanța and back, so I just went to a park near the station to eat my lunch. As I had time, I explored Constanța station and discovered a plaque written in both Italian and Romanian donated by the railway workers of Sulmona in Italy (Ovid’s birthplace) to the railway workers of Constanța (where Ovid died), asking that Ovid inspire them in their work.

My train back to Bucharest left on time and followed the same route as I had come the previous day. Initially, we followed the Danube Canal, which opened in 1984 and links the Black Sea with the River Danube, avoiding the less navigable parts of the Danube delta. The canal joins one of the two channels of the Danube at Cernavodă, where there is a large nuclear power station. The Danube splits into two rivers as it swings north through Romania from the Bulgarian border until reaches the Ukrainian border. The train crossed the second of the two parts of the Danube about ten minutes after the first.

The train made good time as it sped towards Bucharest, such that it arrived at its penultimate stop at a suburban station in the outskirts of Bucharest nearly 10 minutes early. However, on the final run it to Bucharest Nord, it was delayed by congestion and arrived nearly 10 minutes late at about 5pm.

I returned to the same hotel I had stayed in a couple of days previously, to discover they had given me a smaller room this time. I then went out to dinner in the restaurant where I had booked a table after my meal there on Saturday night. As this was my last night in Romania and I still had quite a lot of Romanian lei left, I could afford to splash out. I started with cabbage soup with smoked bacon. I followed this with chicken with sour cherries and had ice cream with fruit for dessert. I started the meal with an interesting Transylvanian beer, before switching to Romanian red wine. Despite my best efforts, I still had about half my lei unused.

In 1983 when I returned to Bucharest, I had carried on that same evening on a night train to Belgrade. There are no longer any trains between Romania and Serbia, so this time I spent the night in Bucharest before catching a train the next morning to Bulgaria, which I will cover in the next blogpost.

Reflections

I was very glad that I had largely repeated my 1983 journey, as it allowed me to see how things had changed. It also means that there is plenty of scope to pay another visit to Romania to visit new places.

I found Romania surprising. Obviously, I did not expect to encounter the food shortages that there were in 1983, but I was pleasantly surprised by the choice of good, reasonably priced restaurants in which to eat every evening. However, in other regards I was surprised how little Romania had changed. For example, Poland is a transformed country compared with how I remember it from earlier times, whereas Romania’s public infrastructure still seems to be crumbling and services slightly chaotic. With the exception of the Bucharest to Constanța route, every train I caught was slower than 40 years ago and none of the stations had modern electronic information boards. Most of the museums I went to were rather old fashioned and in none of them was there an information leaflet or audio-guide available. The cities were traffic-clogged, with little evidence of anyone cycling. One does wonder where all the EU development money, the effects of which are so evident in other former Communist countries, has gone to in Romania.

[To be continued – coming next: Bulgaria.]